This trip to Egypt and Jordan was my first time in the Middle East, and I’ve been thinking a lot about the intersection between religion and politics in the area. In Egypt, Islam is the state religion under the constitution, and about 90% of the population is Sunni Muslim. As a tourist, you see many mosques and hear the call to prayer five times a day. When the loudspeakers are blaring the call, you often see men stop in a nook or alley with their prayer rugs to kneel.

Most of the women you see walking around Egypt wear the hijab (head scarf). Some women (the more religiously-conservative) wear the niqab (full face scarf with only a slit for the eyes). The niqab is controversial, as it’s seen by some as a sign of Islamist, or potentially radical, leanings. In Egypt the niqab is currently banned in public and private schools, and in some universities. The hijab is not as publicly controversial, although there can be disagreement within families. There has been an increase in young women wearing the hijab in recent decades; starting in the 70s and 80s it became associated with fundamentalist movements on university campuses.

There’s apparently a class distinction between women who wear the hijab (generally lower classes) and ones who don't (wealthier women). Some women see it as a sign of oppression. Some well-educated women who don’t wear the hijab are upset that their teenage daughters are now choosing to wear it. A recent trend among young Egyptian women to wear the hijab may be partly a fashion trend. It’s all very confusing to me. I was surprised to learn that, early in the 20th century, elite women in Egypt veiled their face regardless of whether they were Muslim or Christian.

About ten percent of Egypt’s population (over 10 million people) are Coptic Christians. The Copts have a deep and important history in the country, and they contributed the practices of monasticism and asceticism to worldwide Christianity. The Christian religion spread to Egypt in the 1st century AD, long before Islam arrived in the 7th century.

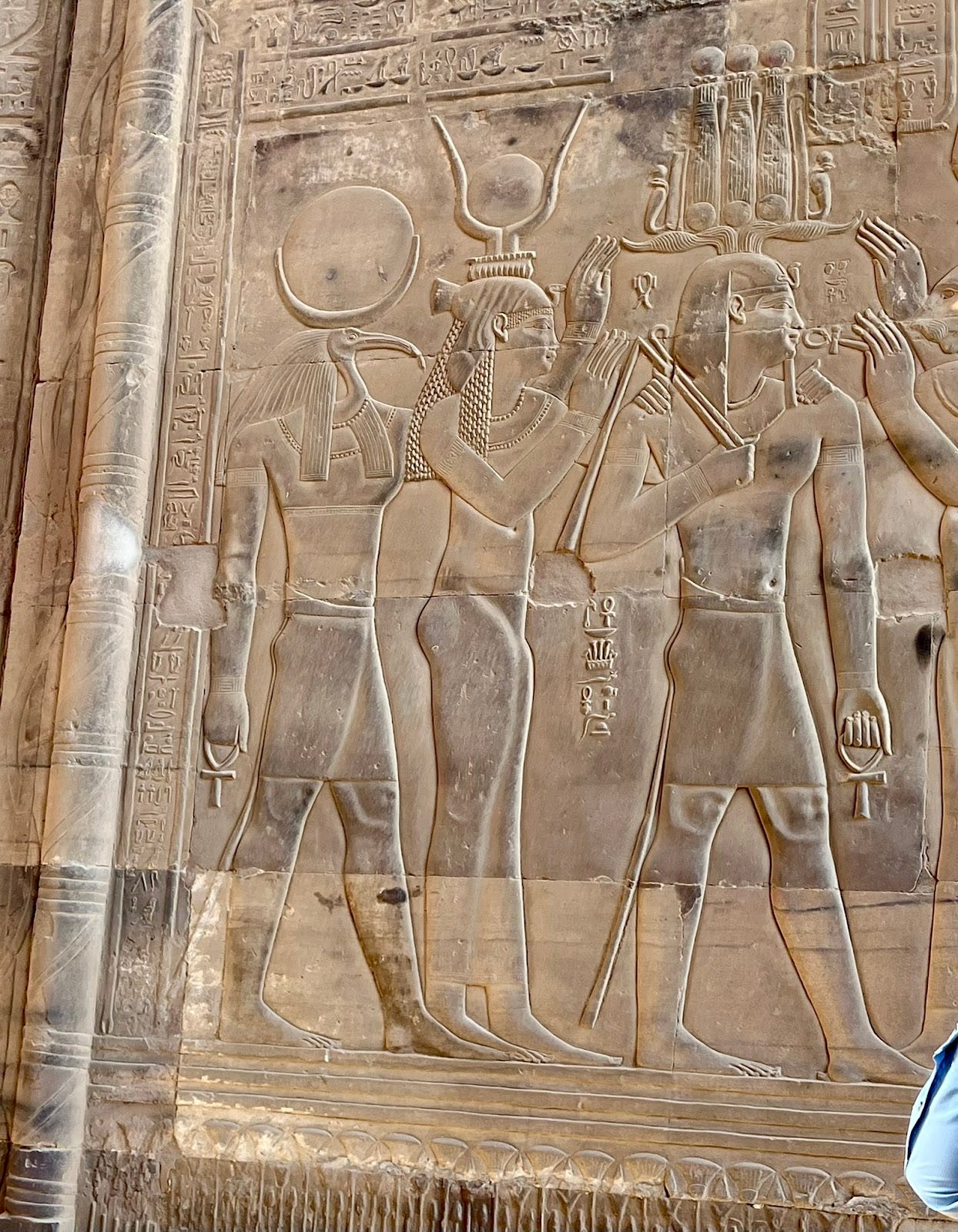

The Christian religion, being monotheistic, was of course different from the polytheistic ancient religion—the people were used to worshipping Osiris, Re, Anubis, Mut, and many more. Yet there were similarities between the two religions that made it easy for Christianity to take hold. Osiris and several other gods were both human and god at the same time, just like Jesus. There was a trinity or holy family among the ancient gods: Osiris, his wife Isis, and son Horus. Many scholars think that the images of Isis (goddess of healing, protection, and peace) holding baby Horus were the models for later images of Mary and Jesus.

Osiris rose from the dead, just like Jesus did. And of course, life after death was an important belief for the ancient Egyptians, thus all the elaborate mummification and objects in the tomb for the next life. So the heaven promised by Jesus was not a new concept for the Egyptians.

It was fascinating to learn how parts of the ancient pagan religion were used in early Christian practices, and the extent to which they still prevail today. For example, the sun disc over the head of certain gods is quite similar to the halo developed in Coptic art. In addition, the early Christians used the ankh — the ancient Egyptian symbol of life— in their art as a cross symbol, and that morphed into the early Coptic cross.

Starting in the 1st century AD, the Romans persecuted the Christians in Egypt. Apparently the Romans saw the Christian monotheistic belief as incompatible with fidelity to the Roman pantheon of gods (whereas the earlier polytheistic beliefs in Egypt were not as threatening). The Copts split with the rest of the world’s Christians in the 5th century over the “single vs dual” nature of Christ. This led to other Christians considering the Egyptian Christians to be heretics, and to more persecution.1

Then the Arabs came to Egypt in the 7th century, and in a few hundred years the Muslims were a majority and the number of Coptic Christians declined dramatically. Many converted to Islam to avoid heavy taxation imposed on them. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Copts really had it bad, as the Christian Crusaders considered them heretics and killed them, and the Arab Muslims treated them as second-class citizens.

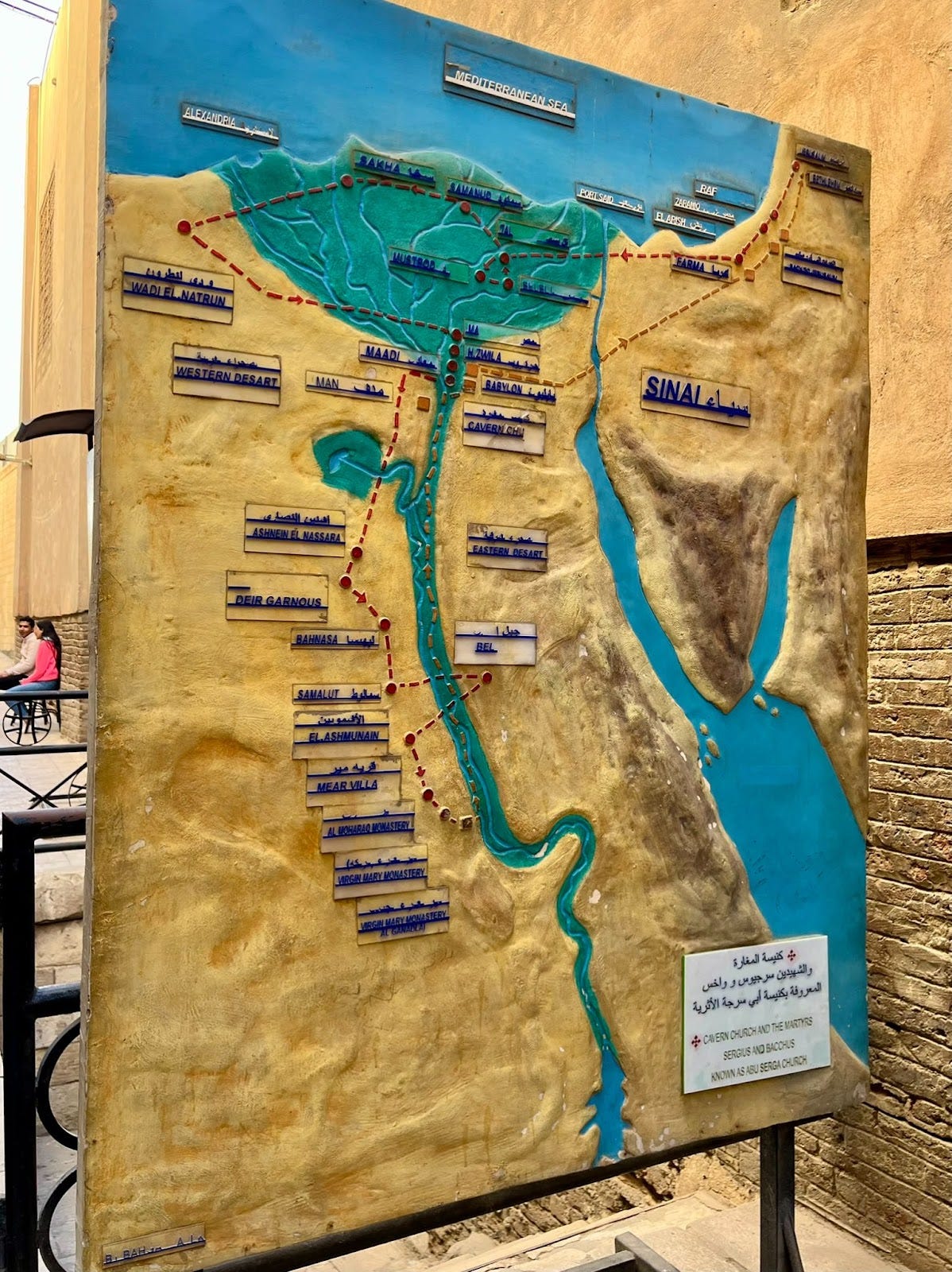

Today, Egypt relies on tourism dollars for its economy. Some tourists visit the sites in Egypt where Joseph, Mary and baby Jesus hid out from the Romans. Pope Francis visited Egypt in 2017 and officially proclaimed these as Roman Catholic pilgrimage sites, but there isn’t the infrastructure yet to support widespread tourism to most of the sites.

But of course most tourists go to Egypt to see the ancient pyramids, sphinxes, and tombs. There’s apparently a love-hate relationship that some Egyptians have with tourism today, because modern Egypt is Muslim, and some Muslims see the ancient past with its plural gods as anathema to Islam. The Coptic Christians, on the other hand, claim a direct link to ancient Egypt (which the Muslim invaders don’t have). Even the Coptic language is similar to and is derived from the ancient Egyptian language.

This may partially explain why the Muslim Brotherhood burned Coptic churches in 2013 after Morsi (the Muslim-Brotherhood elected President) was ousted from power. It wasn’t that the Copts were behind the ousting but that, for many Muslims, the Copts symbolize the opposition to Muslim rule. They stand in the way of the Brotherhood’s vision of Islamic fundamentalism linked with nationalism.2

The Jews in Egypt may have had it even worse than the Christians. The origin story for the Jewish religion is partly based in Egypt and is very important to many Jews. However, the historical accuracy of the Moses/Exodus story is debated, and is doubted by many historians.

The more modern story of Jews in Egypt is not controversial, but it is tragic. There were large numbers of Jews in Egypt dating from at least the Greek and Roman days (330 BC-400 AD), but then the rise of Christianity led to massacres and expulsions of Jews. Later, following the Arab conquest, the Muslims originally tolerated the Jews, but that tolerance went up and down over the centuries. When Israel was created in 1948, anti-Jewish sentiment increased in Egypt, and about 20,000 Jews left the country, many moving to Israel. Following the 1956 Suez Crisis (known in Egypt as the Tripartite Aggression, as Britain, France and Israel attacked Egypt), Nasser’s government claimed that Egyptian Jews could be Israeli spies. The government confiscated Jewish assets and basically forced the remaining Jews to leave the country. From early in the twentieth century through 1948 there were approximately 80,000 Jews in Egypt, whereas today there are reportedly fewer than twenty in the entire country. We visited the lovely Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, which was rebuilt several times to replace the destroyed 11th-century building, but the synagogue is no longer used for religious services due to the lack of Jewish residents.

Egypt’s current government, led by El-Sisi, publicly espouses religious freedom. Although the Egyptian Constitution provides that Islam is the state religion, it also guarantees freedom of belief for Christians and Jews, as well as for Muslims (everyone else is out of luck). But the reality for Christians and Jews is not so great. And Muslims, too, face suppression of free speech. The government, in an attempt to be seen as a secular state and to prevent a threat to its power, has outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood. It generally opposes Islamist parties.3

Religion has long been intertwined with politics in Egypt. Both Nassar and Sadat increased the role of the Muslim religion in Egyptian society. That contributed to the rise of the fundamentalist (Islamist) movement. Fundamentalist members of the military turned against Sadat and assassinated him after he signed the 1978 Camp David Accords and a 1979 peace treaty with Israel that demilitarized the Sinai and recognized the state of Israel.

There are still Egyptians today who are Nassar supporters, and some who are Sadat supporters, despite the fact that both presidents are long dead. (There don’t seem to be any vocal Mubarak supporters–no surprise). These political factions vary greatly in their beliefs, and feelings still run raw, at least for older generations, who lived through the many wars that Egypt has engaged in.4 It’s hard to tell how people feel about el-Sisi, who has been President since 2014, because the press is restricted, and elections are not free or fair.

Religion has been the source of so much antagonism in the world. No wonder we tourists love to see the remnants of an ancient religion that no longer exists — it’s safe and (relatively) noncontroversial to visit the pyramids and the Valley of the Kings. But it was equally fascinating to me to learn about the history and current status of the modern and ongoing religions in Egypt.

The more I learn about other religions, the more I see their commonalities. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, for example, all have light and love as central concepts. The more we know about other people, the more we can try and understand them. Try to work towards reconciliation. Towards peace. Isis knows, peace in the Middle East is sorely needed.

Previous post on Egypt: Funky Tut and the Afterlife

Photos by Jill Martin, except where otherwise indicated

Sources, and for further reading:

https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/exodus-era/4919-top-ten-discoveries-related-to-moses-and-the-exod Doubting the Story of Exodus - Los Angeles Times (2001) The Story Behind the Coptic Cross Tattoo | Egyptian Streets Egypt - Egypt under Rome and Byzantium, 30 B.C.-A.D. 640 https://generisonline.com/freedom-of-speech-and-censorship-laws-in-egypt-an-overview/ International standards for free and fair elections are not part of the process in Egypt – Middle East Monitor Egypt’s Christians face backlash: Coptic churches are attacked as the violence among Egyptians widens( 2013) Sisi Can't Erase the Muslim Brotherhood From Egypt's History https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Egypt Country Update: Religious Freedom Conditions in Egypt (2023) Wars of Modern Egypt

Copts believed in one nature (God) with two aspects (God and man), whereas the other Christians ruled at Chalcedon that Jesus had two natures, both human and god. This split may have arisen over a misunderstanding based on wording/language usage, but there seems to be no way to reconcile now. The Copts have remained separate from other Christians and have their own Pope, the Patriarch, now based in Cairo.

For an excellent analysis of the Arab Spring in Egypt, see The Buried by Peter Hessler. The Dartmouth professor accompanying our alumni group, Mike Mastanduno, suggested we read this book prior to our trip. I recommend it for anyone traveling to Egypt, and I also recommend this professor for any Dartmouth alums considering a trip in the future to any country for which he is the accompanying professor.

When visiting a Coptic church, I was shocked to see that on one wall where there were photos of the last six presidents, there is no photo of Morsi– they just skip over him, despite the fact that he was elected.

Since WWII, Egypt has been in wars in 1948-49, 51-52, 55, 56, 62, 67, 68-70, 73, 77, the 90s, and 2011-2014.

Jill- Thanks for sharing your anecdote. Particularly about the class distinction of outerwear and its implications. I think it’s hard for people to believe that there are often modern values now attached to certain traditions and your article illustrates that beautifully.

Wow, learned a lot from that. Thanks, Jill, for that compassionate history lesson. I’m with Isis!